Introduction

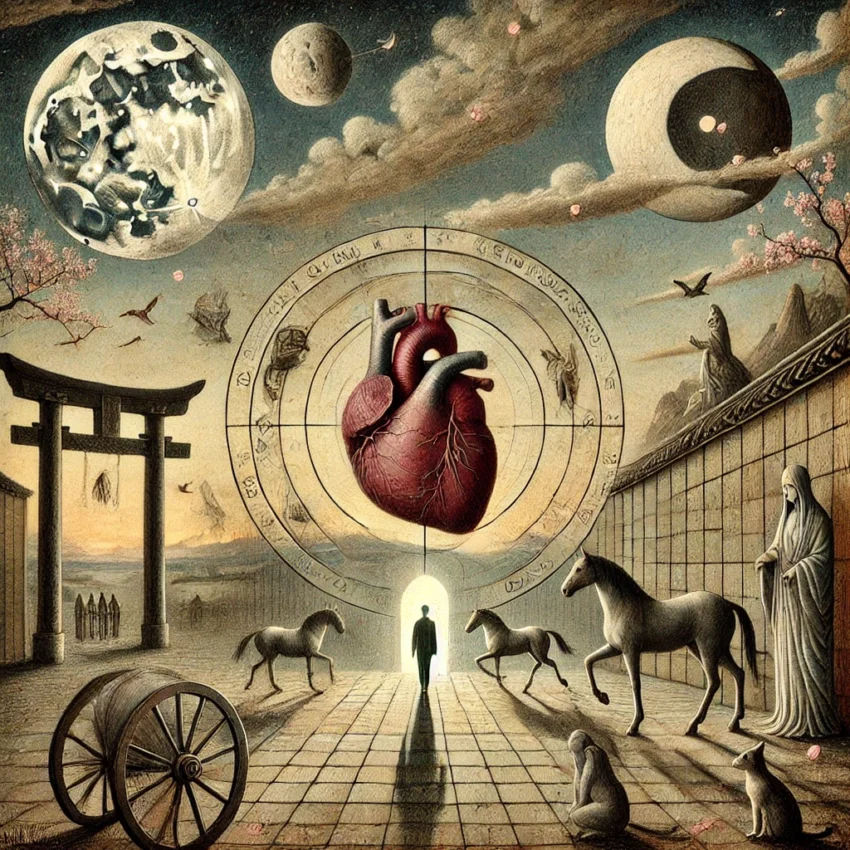

Haruki Murakami is one of the most significant contemporary Japanese novelists. While he never directly addresses medicine in his works, health-related themes frequently appear as metaphors. In his writing, the body and its lived experiences are consistently connected to trauma, memory, and the unconscious. These connections extend into fantastic, paranormal, and cosmological dimensions, transforming symptoms into bridges toward alternative realities.

The Body as the Site of Psychic Trauma

In Murakami’s novels, the body functions not as a biological system but as the site where wounds of the soul manifest. This approach parallels principles of psychosomatic medicine, which recognizes that inner conflicts—particularly unprocessed emotional losses—often surface as physical symptoms. Anorexia, insomnia, loss of desire, and isolation become physical expressions of existential pain. Perhaps the most striking manifestation of these traumas is the loss of one’s shadow, representing a true amputation of an inseparable part of lived experience.

The loss of shadow

In the novel “Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World” (1985), an anonymous man becomes involved in an experiment on consciousness and memory. He begins to lose his memories (Hard-boiled Wonderland). In a parallel dimension, the man arrives in a walled city without doors populated by pale shadows and silent horses. He realizes that his shadow has been amputated, an operation necessary to live in that world (The End of the World).

The loss of shadow symbolizes a removal of pain through a “surgical intervention” on the soul. The body without shadow continues to function, but the identity is fundamentally altered—a true “loss of self.”

The Heart as Spiritual Center and Source of Rhythm

In Murakami’s works, the heart functions as an internal metronome—a constant reminder of one’s existence in the world. The heartbeat serves as tangible proof of being alive. In “Kafka on the Shore,” the protagonist experiences his heart beating “like a drum in the forest.”

The heart also appears as a vulnerable organ reflecting its owner’s psychological state. Rather than suffering when love is lost, it withdraws and shuts down metaphorically. In “Norwegian Wood,” Watanabe describes his heart as “a piece of frozen meat,” illustrating its numbness and his disconnection from the world. Thus, the heart transcends its biological purpose of “pulsing” to become the repository of memory and desire.

This duality—the rhythmic, pulsing heart and the suffering heart—portrays an organ both sensitive and resilient, resonating with psychic forces, music, invisible energies, and fate itself.

The Absence of Medicine

In Murakami’s fictional universe, conventional medicine has no substantial presence or purpose. Rather than healing, it tends to isolate. In “Norwegian Wood,” the clinic exists as a sterile environment, detached from normal time. Murakami doesn’t necessarily distrust medicine itself; instead, he portrays it as limited, unable to address emotional suffering. Since medicine cannot heal the soul, it remains peripheral to his narrative concerns.

Healing in Murakami’s novels emerges from elsewhere: through everyday rituals such as cooking, listening to music, or writing. These activities become therapeutic because they serve as ceremonies that bridge the disconnect between body and mind.

Healing Transcends the Physical

In “Kafka on the Shore,” Takata performs a chiropractic treatment for truck driver Hoshino’s back pain. Though extremely painful, the treatment functions as more than physical therapy—it serves as an initiation ritual. Through this suffering, Hoshino undergoes a profound transformation, emerging as a more aware and empathetic person. This episode illustrates how physical healing in Murakami’s world simultaneously operates as existential transformation. Healing isn’t merely a return to normalcy, but a passage through a threshold. Individuals don’t heal to revert to their former selves: they heal to become something new.

The Body as a Vehicle to Other Dimensions

Murakami’s vision of the body extends beyond its connection to the mind—the body serves as a vehicle for accessing other worlds, systems, and dimensions. Like a transport that, triggered by specific events or stimuli, carries us to invisible and unknown realms.

In “Kafka on the Shore,” Nakata suffers a childhood trauma that leaves him unable to read or write, erasing his previous knowledge. This emptiness, rather than limiting him, opens doors to extraordinary abilities—he can communicate with cats and perceive what others cannot. Instead of being a permanent disability, Nakata’s condition serves as a transition into a new reality.

Elsewhere in the same novel, a lightning strike propels the protagonist, Tamura Kafka, on an inner journey through a mythical dimension where he confronts his family’s destiny.

Similarly, in “1Q84,” the pregnant protagonist functions as a kind of antenna, sensing cosmic shifts manifested by the appearance of two moons in the sky.

In “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle,” the protagonist undergoes states of deep meditation and introspection. These states coincide with an unexplained ear infection, as though his body senses and manifests the transformative process through this specific physical symptom.

Trauma often catalyzes this transformation of the body into a dimensional gateway. Its symptoms, depression, memory loss, create fractures in the continuity of reality, enabling resonance with other dimensions. This reveals a body-psyche-universe continuum whose disruption unveils new cosmological realities and existential conditions.

Conclusion

Murakami’s medicine goes beyond normal physiology: it is a gateway that exposes the body to forces that transcend physiology. Pain, madness, sleep, and memory loss are not negative events but become rites of passage that take us into new dimensions, with talking cats, worlds with two moons, bodies without shadows, and we listen to our own pulsing heart as an affirmation of self. And then perhaps we begin to heal, and our heart continues to beat, even when everything else falls silent.

Bibliography

| Original title (Japanese) | English title | Year |

|---|---|---|

| 世界の終りとハードボイルド・ワンダーランド (Sekai no Owari to Hādoboirudo Wandarando) | Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World | 1985 |

| ノルウェイの森 (Noruwei no Mori) | Norwegian Wood | 1987 |

| ス푸트니크の恋人 (Suputoniku no Koibito) | Sputnik Sweetheart | 1999 |

| 海辺のカフカ (Umibe no Kafuka) | Kafka on the Shore | 2002 |

| 1Q84 | 1Q84 | 2009–2010 (books 1–2), 2012 (book 3) |

| 城とその不確かな壁 (Shiro to Sono Fukujōna Kabe) | The City and Its Uncertain Walls | 2023 |